红色的门

以下是转载班敦士教授在澳大利亚历史移民网络(Australian Historical Migration Network)发表的文章。 (文章用英文撰写)

The Red Doors

By Denis Byrne

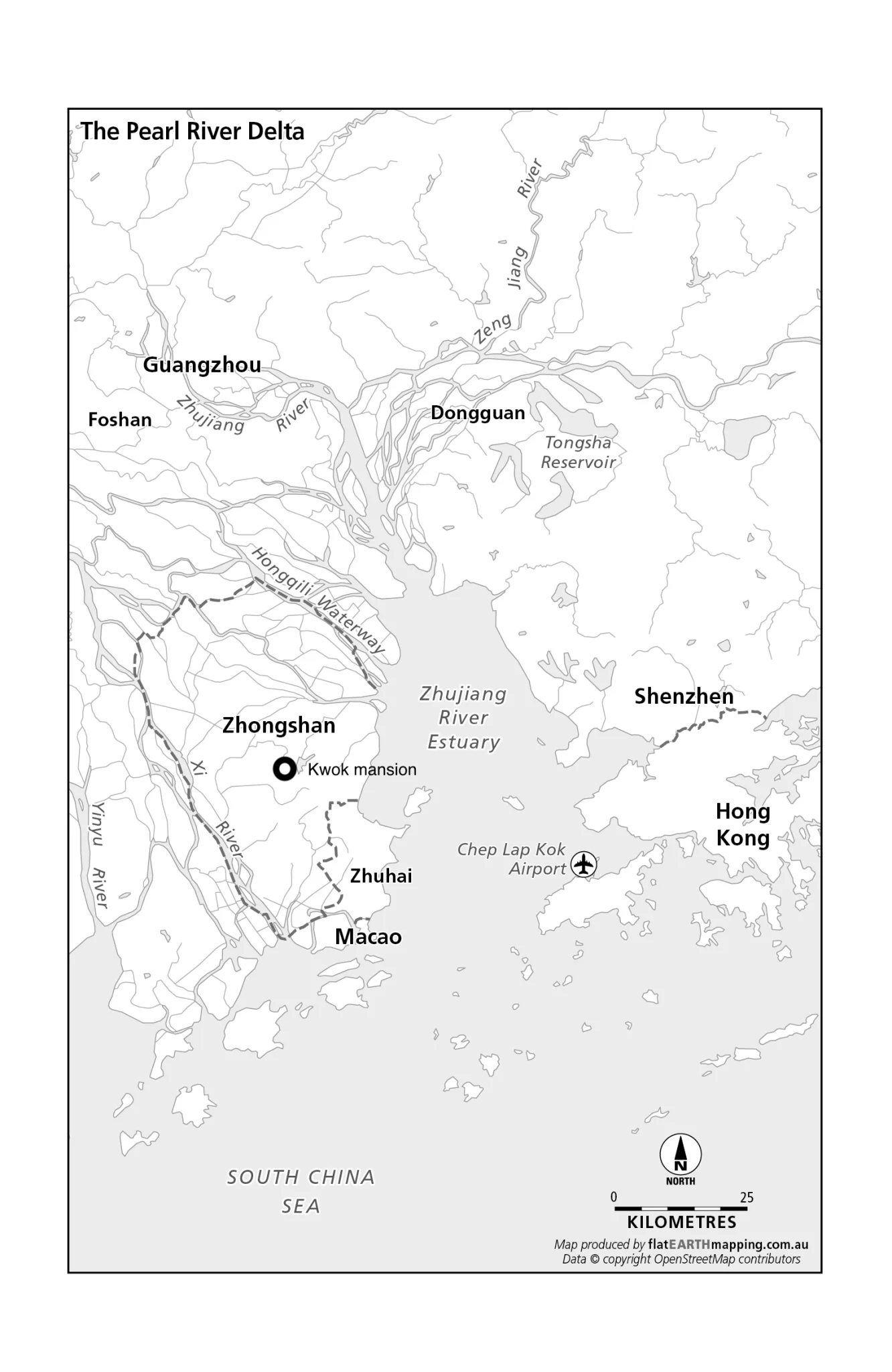

In the village of Zhuxiuyuan, in China’s Guangdong Province, there stands an Art Deco mansion that was built in the 1930s by the Kwok (郭氏兄弟) brothers, founders of the Wing On department store chain (永安集團), who had begun their entrepreneurial careers in the 1890s as banana traders based in Sydney’s Chinatown. The three-storey mansion survived the Japanese occupation of Guangdong (1939-1945) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and is now protected by the Chinese government as a heritage site testifying to the history of the enduring ties between members of the Chinese diaspora and their home villages.[1]

But while the Kwok mansion’s foundations are sunk in the soil of Zhuxiuyuan, which is situated in Zhongshan County, the mansion can nevertheless be seen as part of Australia’s heritage record. Like the hundreds of other houses built in their home villages in Zhongshan by those who migrated from there to Australia between the 1840s and the 1940s, the Kwok mansion testifies to Australia’s history as a migrant receiving country. What it especially illustrates is that migration should not be thought of as a one-way journey. The migration narratives of those who have come to Australia very often include return visits to their homelands and the sending of remittances back to those who stayed behind. The migration corridors that connect Australia to migrant-sending countries have been characterised by a backwards and forwards flow of people, ideas, goods, money, letters, photographs, and other things. Over time, this has given rise to a material heritage that is truly transnational in scope.[2] It is not a question of whether the Kwok mansion ‘belongs’ to China or Australia, it belongs to a heritage of migration that connects the two.

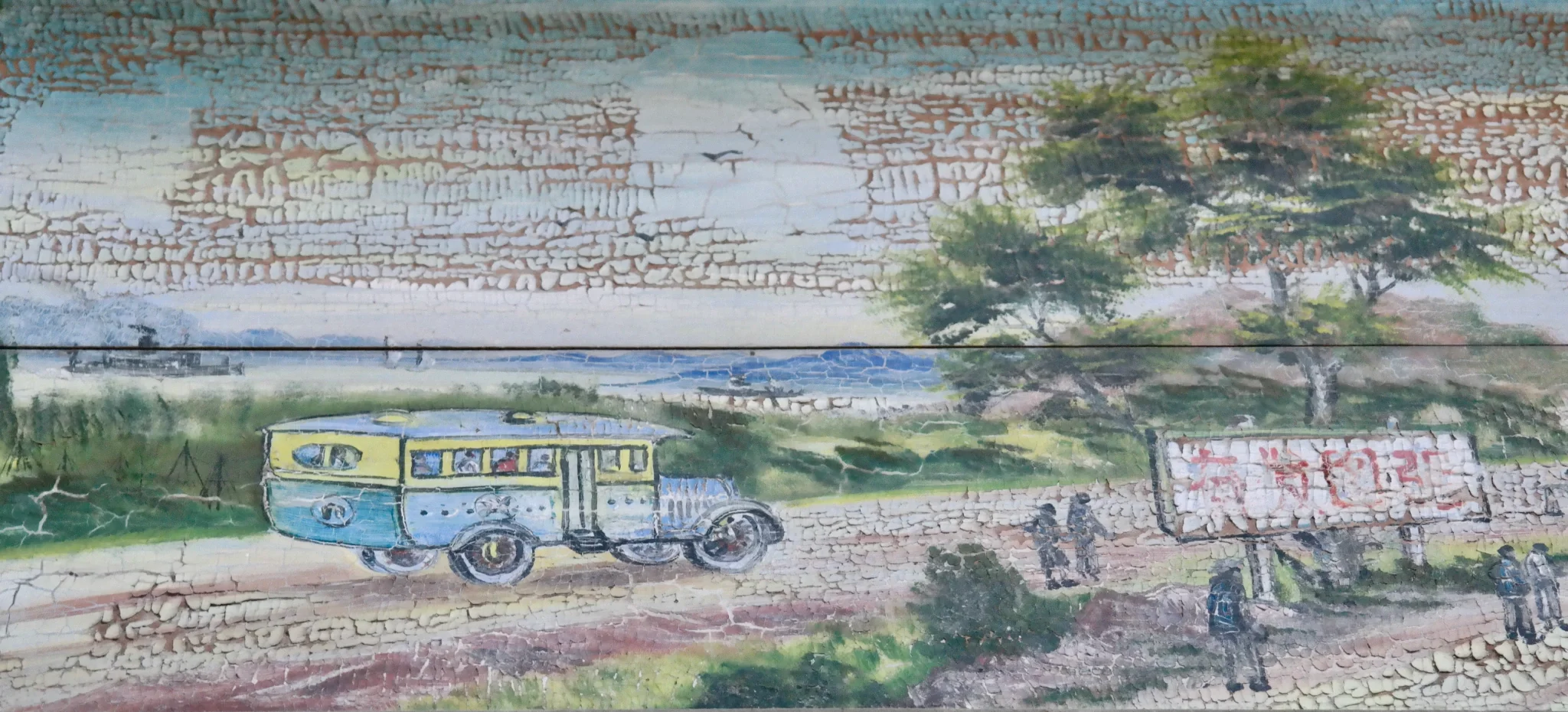

The large entrance foyer of the Kwok mansion has reception rooms on either side that are separated from the foyer by doors whose top halves consist of glass panels set in lattice screen wood framing. The lattice screen framing is one of the only features of the house that references traditional Chinese design. This contrasts the other migrant-built houses in Zhongshan in which traditional-vernacular design elements, such as tiled gable roofs and carved wooden screen walls, are combined with such non-traditional elements as reinforced-concrete pillars and floors. Many of these houses contain wall paintings, some of which are in a tradition style, depicting fruit, birds and plants believed to be auspicious, while other paintings in the same houses depict motor buses, steam ferries, and the ocean-going steamships that by the early 1900s carried Chinese migrants to Australia and back to China for visits.

In the case of the doors in the Kwok mansion, even the lattice screen design seems not to take its inspiration directly from traditional Chinese art and craft, it is more likely to have been inspired by a European Art Deco style that was influenced by Chinese art and craft. The Art Deco style, which emerged in Europe in the 1910s, is also, and on a much larger scale, seen in the ‘sunburst’ motif on the tower that rises from the roof of the house. The ‘Chinese’ motifs in the stained-glass windows above the doorways in the foyer, one of which depicts a landscape with a Chinese pagoda and another shows two figures in traditional Chinese garb about to cross a moon bridge, again have more to do with Europe’s taste for Chinoiserie than with the art of China itself.

Like the house as a whole, the doors in the Kwok mansion foyer make a statement about the modernity and the social status of the Kwok brothers. Just like many Chinese Australians in the early twentieth who sported modern hairstyles, wore the latest fashions, played tennis, and drove the latest-model cars, the houses they built in their home villages in Zhongshan County expressed a modernity that had become associated with migration. As well as their walls paintings of buses and steamships, from the 1920s the houses were increasingly wired for electricity and contained radios. Pedal operated Singer sewing machines, often brought as gifts by returning migrants, were de rigueur items in the houses and were used for making modern-style garments, such as the cheongsam, that were appearing in China around this time.

In 2015, when I first visited the Kwok mansion, I noticed that the cream-coloured paint on the foyer doors was flaking off in places to expose an underlying layer of red paint. Without being able to tell when the red had been overpainted with cream, I assumed it had done at some point over the previous couple of decades as part of restoration work carried out to prepare the house for visits by tourists. Visitors would include the many Chinese Australians and their descendants who by the 1990s were travelling to China in a form of tourism that involved visiting their ancestral villages.[3] For many of them, it was their first opportunity to see the villages they had known only from stories told to them in Australia by their elders. The Kwok mansion became key stopping place on tours which, for many returnees, also involved attempts to locate the houses their migrant forebears had built but which had been lost track of during the Japanese occupation of Guangdong (1938-1945) and the ‘closure’ of China during the Maoist era (1949-1976). During these years it had been difficult or impossible for Chinese Australians to make return visits to Zhongshan.

The red paint on the doors of the Kwok mansion may well date to a time when the mansion was used as a government office in the period after it was appropriated by the state in 1949. Ninety percent of houses belonging to the families of migrants in Guangdong Province were confiscated at that time and allocated to villagers classed as poor peasants and landless labourers. The larger houses were sometimes divided to accommodate multiple families or were used as government offices, military accommodation, or for other public purposes. This was a radical reversal of fortune for those with connections to the diaspora. The lifestyle and houses of those villagers with diaspora connections had once been a source of pride and elevated social status for them and had provoked envy among poorer villagers without migrant ties. Now, in the 1950s and 1960s, they intimated bourgeois decadence and counter-revolutionary leanings. The dispossessed, tainted by their diaspora associations, were consigned to life at the bottom of the new social order and some, classified as landlords at the beginning of the land reform campaign, were executed.

The layer of red paint, which today shows through the later layer of cream paint on the Kwok mansion doors, symbolises for me this project of socio-economic levelling. The four Kwok brothers who had built the mansion in Zhongshan for their father, Gock Pui Heen (郭沛勳), were not directly affected by the Communist Revolution because they lived in Hongkong and Shanghai, where their business empire was based. They only stayed in the mansion during visits back to their home village. Ownership of the mansion was later restored to them by a government wanting to encourage diaspora investment in China.

In the present-day villages of Zhongshan it is not easy to find tangible remains of the events of the Mao era. You see the occasional red star in moulded stucco still attached to the façade of a village office, or the mouldering ruins of a lineage hall that was repurposed as a communal dining hall during the period of collectivization (1958-1961). Most such halls have, however, now been restored with funding provided by lineage members overseas, including those living in Australia. The Communist Party does not wish to draw attention to what it euphemistically refers to as Mao’s ‘mistakes’, most notably those represented by the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution and which now comprise an embarrassing heritage.

Instead, in what one commentator has called ‘a great leap backwards,’[4] emphasis is placed on pre-1949 heritage sites, including those of the Republican era (1912-1949). These include sites associated with the war against the Japanese, but they also include the grand houses built by migrants such as the Kwok brothers in their home villages. But physical traces are not easy to erase, as witnessed in the case of the Kwok mansion doors whose red paint is busily resurfacing. And even if it is painted over again it will still be there, like an archaeological layer, ready to testify.

[1] Denis Byrne. 2022. The Heritage Corridor: A Transnational Approach to the Heritage of Chinese Migration. London: Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/The-Heritage-Corridor-A-Transnational-Approach-to-the-Heritage-of-Chinese/Byrne/p/book/9780367543150

[2] Denis Byrne. 2020. ‘Dream houses in China: migrant-built houses in Zhongshan County (1890s-1940) as a “distributed” form of heritage’, Fabrications 30(2): 176-201. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10331867.2020.1749218?journalCode=rfab20

[3] https://www.heritagecorridor.org.au

[4] Lingchei Letty Chen, The Great Leap Backward: Forgetting and Representing the Mao Years (Amherst NY: Cambria, 2020).

附加信息

这篇文章可以通过以下链接在澳大利亚历史移民网络 (AHMN) 的网站上找到:https://amigrationhn.wordpress.com/2022/05/26/the-red-doors/

更多关于郭氏大宅和竹秀园学校的信息,请参阅《中山日报》发表的这篇文章(中文):https://zsrbapp.zsnews.cn/mobile/newsDetail/#/616809